American Basics

(Image from the cover of the reissue box

for the Anthology of American

Folk Music)

Treasures from the American

Attic

(The Song of the Blue Catfish)

"Capital H" history is a small boat floating on a river of unrecorded stories. (That's the best metaphor we've come up with so far.) The only way to chase what really happened is to dive in. You may have to swim against the current, and the waters may get murky. But if you listen for the songs people sing when they're working and playing you'll find your way.

Work calls music to your head. If you're drowsy or bored, you can try mental multiplication or reciting "The Song of Hiawatha," but you're likely to wind up hearing a common song on your internal radio. It doesn't matter if you're hoeing trees or chopping crops, driving a machine, snapping beans or dressing chickens, the rhythm of the work will start to lay down a beat. You'll start to improvise words around a phrase or tune you've heard. If the field you're plowing is in a cubicle, and you drive a keyboard, the music might get muted by the telephone, but you can still find yourself keeping the beat with a pencil.

And the music on all those internal frequencies is the heartbeat of who we really are as a people—forged from the many, the cast-out and the taken. On any given day it's the soundtrack for our collective unconscious, and it helps to define us. It's not mannered, approved, or even written down until it's already a part of us all. A lot of the time it isn't something you would sing to your average grandmother. Soldiers don't march 30 miles with full packs humming Beethoven, and hard work has always had a remarkably leveling effect on adjectives.

Some things don't change.

Sometimes we forget.

Sometimes you have to very nearly lose something to appreciate its worth. And sometimes you can feel it slipping away again, but you don't know what to do.

Some memories, then...

Remembrance is better triggered by smells and sounds than by sights. Looking back at the early 1950s, when a lot of us were attending those first-through-eighth-grade, one-room schools scattered across the plains, our recall of the words in the textbooks is a little blurry. But the smell of a coal oil-burning stove or the sound of records played at 78 revolutions per minute on a hand-cranked phonograph can call the room back entire.

We certainly didn't know it at the time, but we were listening to our history's official soundtrack when we opened the door on that five-foot tall cabinet, picked a record, cranked the handle, replaced the needle in the swiveled-up holder and set it carefully down on the spinning shellac. There wasn't a volume control, really. There wasn't any electricity yet out there, so the amplification was megaphonic. And there was a divide between those tall enough to reach the playing arm unassisted and those who needed a stool. "Big" kids could place the needle, but the little brothers and sisters who rode to school behind the saddle were usually limited to turning the crank.

Selection was also limited. The permanent collection would be donated by members of the community, after careful screening. Then there were the records that came with the "reading books" in the circulating wooden boxes from the County Superintendent of Schools. Memory serves up Sousa marches and Stephen Foster songs and Caruso, and "Roamin' in the Gloamin'," (which took a lot of figuring out) and a constant chorus of crackles and pops.

The world was pretty small. Some townships never mustered more than eight students in the entire school.

There was no television yet. The newspaper came in the mail—three days after printing. Radios in cars were for "town folks." Radios in living rooms used batteries, and a few families had 32-volt DC systems, driven by a windcharger and rows of 4-gallon battery jars in the storm cellar. The one radio stay tuned all day, usually by paternal edict, to WNAX for the market reports and the evening radio dramas, and kids were not to fiddle with it.

Things were a little different "in town." Especially if you had an uncle who loved jazz and swing and gadgets. It was plainly not the same music we had at school. And his electric changer was one of the few around that actually dropped a new record without helping the turntable along with your hand when it cycled. You learned the invisibility trick (if I'm reading a book they can't see me), because some of the grown-ups pretty clearly did not approve of you hearing "that stuff." Which guaranteed that you would pay careful attention...while occasionally turning a page... Perhaps "trans-parently" is a better word...

Variations on the invisibility trick also came in handy for community get-togethers. Grown-ups acted different sometimes, and you finally figured out that there was another world behind the one you saw everyday. There were times when the rules changed for a few hours, or even a day. It might be at a barn dance, with the sweet and tantalizing smell of whiskey outside in the shadows. It might be in the triumphant twilight of a blistering summer day spent beating back a prairie fire before it took some family's cattle and buildings. It might be at a baseball game outside the Grange Hall, or lazing (transparently) beside a PWA dam—listening to your Dad and Uncle—fishing for a mess of bullheads with a bamboo pole. It might come with unexpected visitors, when the grown-ups took the evening breeze outside the house and the other kids were racketing through the out-buildings. A story would be told, perhaps. Or a song would be played or sung... And then one night we found out that there was a whole 'nother set of rules for something called a shivaree, and some very interesting songs as well...

We didn't know that John and Ruby and Alan Lomax had been recording the music of regular folks where they lived and worked for over 20 years. We might have heard the name Bessie Smith, but we sure weren't told about Memphis Minnie. Radio had the occasional musical broadcast, but we were more likely to hear Lawrence Welk than Duke Ellington.

We didn't know that the steep stairs to the attic of our American musical heritage were seeing fewer and fewer footprints in the dust. We didn't know about the tunes that were missing from our mental sound track, or the truths they carried. And we didn't know that there was a man named Harry Smith who was about to change all that, if he could.

But we knew something was happening.

1952.

That was the year a lot of us were taken into town to see "The Greatest Show on Earth." Delight and anticipation at seeing a real movie were dashed after hushed conversations between parents and uncles and aunts. A new epidemic of polio had arrived. The close confines of a theater filled with a crowd of strangers were just too risky. We didn't understand...

The 47th (Viking) Division of the National Guard had been called up for the Korean War in 1951, and people started looking more closely at the black-bordered casualty box, centered on the front page of the Argus Leader. Kids started picking up new phrases... Bloody Ridge... Chesty Puller... Heartbreak Ridge. SFC John R. Rice, killed in Korea with the 1st Cav, had been buried with honors at Arlington the previous August, by Harry Truman's order, after a cemetery in Sioux City had refused him burial because he was a Winnebago Indian. Dorothy Mayner took the torch from Marian Anderson and a black soprano finally sang in Constitution Hall in the nation's capital. She sang Mozart. Emmett Till was 13 years old, growing up in Chicago.

Elizabeth became queen. Britain got the atomic bomb. Truman signed the treaty ending the war with Japan. Hussein became the king of Jordan. The French opened a huge offensive against General Giap's Viet Minh. Nixon gave his "Checkers" speech. Eisenhower beat Stevenson. John F. Kennedy won his first election to the Senate from Massachusetts, beating incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge.

All those big pieces of big history would change the plain lives that would be later remembered in spoken stories and small newspapers. And somehow—in that same year—Harry Smith cracked open the attic door, cleared a path through the sousaphones and minstrel trunks and gave us back our recorded common heritage. It took a few more years before the folk music boom and the blues "revival." It took a while before the field recordings by the Lomax family and their associates were really appreciated. But the trickle begun in 1952 grew and nourished us, and the river ran full under History's boat. It's still important. We're initially offering the Anthology and a small blues collection, dipped from that stream. Jazz will follow next and maybe even bluegrass, traditional and folk. And more recent blues artists.

So the question arises: "What the heck does the ?"blues"? have to do with the Northern Plains? And why are you starting with that stuff?"

Ok, two questions...but good ones.

One answer to the first one is the Wisconsin Chair Company. And riverboats. And if you mark the eastern edge of the plains somewhere around Chicago...

The second question? Well...because we really like this stuff... And, the US Senate has designated the end of 2003 and the beginning of 2004 as "The Year of the Blues." (Honest! We couldn't make most of this stuff up.) And because we stand on the shoulders of all who came before, not just the people you can find in books. And because those stairs to the attic are getting really, really dusty again... Anyway...

The Wisconsin Chair Company?? Yep! In Port Washington and Grafton, right north of Milwaukee, in the early 1900s. They made phonograph cabinets for the Edison Company, and one way to sell a fancy item like that was to throw in some records. So, in about 1917 they decided to start a record label—called it Paramount. Only in America... By the 1920s and early 1930s over a quarter of the blues records sold in America were on Paramount, cut and pressed in Ozaukee County, right north of Milwaukee. And you are not going to believe who came up on those old roads and railbeds from Texas and Mississippi and the rest of the country.

Also, in about 1917, Louie Armstrong was playing summers on the boats running the Mississippi between New Orleans and Saint Paul, before King Oliver called him up to Chicago. And blues and jazz came to "the territories" and to the people who rode the horses and drove the tractors and snapped the beans, and made the history that didn't much get written down...

So. If history is written by the winners, do the deeds of the losers disappear? If the winners' history has a sound track, do the other songs fade away? Does the music of the people who never owned a bank or a railroad, never made the textbooks, and never made a fuss lose meaning? What of the messages their songs carried?

And how do you really figure out who won...and who didn't?

Here are some parts of the soundtrack to the hidden history of the continent...

If you are looking for any sort of 'definitive' "Blues" or "Folk" or "Roots" Collection, you are in the wrong place. Nobody around here is a purist, and our loop is cast far too wide for the cognoscenti who are. We're a heck of a lot more interested in how pieces fit together than in definitions that might leave out part of the puzzle. Some folks would say that some of this is "country" or "old-time" or "jazz" or something else. That's ok. Please remember the rules around here. Anything on these shelves has to also be in our real library, has to be something we listen to, and has to be something we recommend to our friends. For this collection we added a further rule—what did we reach for when our kids said, "What's so special about this 'Blues' or 'Folk' stuff?" And what has come out since then that we're holding back, waiting for the same question from our grandkids... (although some of it's gonna get held back 'till they're quite a bit older...)

It should be clear by now that we spend some time around here asking the question, "What happened? How did we get here? And why don't some of the pieces we're taught seem to fit together?" Ok, ok... three questions. Sheesh. There seem to be a whole string of connections between the emergence of mass media and changes in its technolgy, hidden history of the American folk, demographic flow of the nation, and the tunes that come into our collective head, unbidden. And this includes a series of really dramatic changes in the mid-1950s. So, here are some people and some thoughts that might be pertinent to the issues. As time goes on, we'll also recommend and offer recordings to save you some time if you decide to do your own digging.

Please note that the order in which the albums appear is a little rough. There are a lot of collections, and an attempt was made to put them in the order the earliest inclusions were recorded, but even that isn't strictly observed. And please remember that the comments are our opinions. As said elsewhere, opinions are a lot like armpits. Everybody ought to have at least two, but that doesn't mean they should necessarily be shown in public. Yours may differ. Great! The important thing is the music, the moods and insights, and the artistry on these shelves. We will be including samples of some songs, as soon as we sort out the legalities.

The American Basics Collection—Shelf One

Ma

Rainey

Ma

Rainey

(We recommend:)

1992 Milestone Records release on CD

Produced by Orrin Keepnews

(Cover image is from the CD)

Ok. Lets start right here.

The folks that hang around the Archive Project are "neck-down" blues and jazz fans. Most of us wouldn't know a flatted seventh from a fork lift. We're not players (although Arlo has been known to deliver a bent, screaming guitar lead or two, and Nathan has an historical penchant for showing up in small clubs and playing mouth-harp with bands on open-mike nights—but we're not players). And we're sure not musicologists.

On the other hand, we listen pretty good.

And we know enough about how things spread from person to person, in the great American underground, to doubt that you can draw straight lines from the Delta to Memphis to Chicago in a conversation about the music and encapsulate anything as amorphous as the blues. What about Georgia? What about Texas? What about Indianapolis? What about Ozaukee County?

And what about the women?

We weren't around, but it seems to make sense that "THE BLUES" (as a form) probably coalesced in the late 1800s. Then flat disk records were introduced in 1902, and even Tom Edison had moved to them by 1913. In 1917, the first blues recording to sell a million copies was made. William Christopher Handy had written it in a Memphis bar on Beale Street, called PWee's (Pee Wees's). [See the picture below, after the Memphis Jug Band material.] For the record, PWee's was owned by an Italian immigrant, according to our sources. Handy had to publish the song himself, in 1914, when nobody else was interested. It was first performed in public by Ethel Waters in about 1916. And in 1917, it was recorded by Sophie Tucker and sold over a million copies. It was, of course, "St. Louis Blues."

Sophie Tucker??!!?? Well, yeah... that's the story we got. In 1920, Mamie Smith recorded "Crazy Blues" for Okeh Records, and became the first African-American artist to take a "blues" song over a million copies sold (reportedly over two million eventually). Some say it was the first "race" record. It sure opened things up.

Gertrude Malissa Pridgett had been born in Columbus, Georgia in 1886. In about 1904, she married William "Pa" Rainey, a featured dancer, comedian and singer with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels, one of the more popular touring shows. "Blues" wasn't on the menu of the minstrel circuit...it was "folk" music from the rural areas of the country. Supposedly, the young Mrs. Rainey was working a show in a small Missouri town when a girl came into the tent one morning and offered a song about a man who had left her. It had a totally different sound. "Ma" learned it and began to use it as an encore, and got a huge response, but didn't know what to call the sound. One day, goes the story, she responded to the frequent question, "What is that stuff?" by saying, "It's the blues." Who knows...

By 1914-1916, the act was billed as "Rainey and Rainey, Assassinators of the Blues." By December of 1923, when she cut her first record, she was on her own, billed as "Madame" Rainey, with a headband, gold and diamonds, feathered boas and a stage band of her very own.

That first record?? Well, remember the Wisconsin Chair Company and Ozaukee County? Yup. Gertrude "Ma" Rainey laid down more than 90 "sides" in a five-year recording career and every one of them was for Paramount Records, of Grafton, Wisconsin, employing studios in Chicago and elsewhere. The first one was called "Boweavil Blues." She was called "The Paramount Wildcat."

Her later accompanist and musical director was a young man named Thomas Dorsey, of whom we're going to see a whole lot more on these shelves. He was also known, in the years to follow as "Georgia Tom" Dorsey. For now, it need only be said that by the time Ms Rainey quit recording he and Tampa Red were the original "Hokum Boys," and a whole lot of folks believe that he cut the template for Gospel singing. (And if you don't think you know what "hokum" is, just stick around.)

In about 1933, she retired from the road and returned to Columbus, Georgia—outside Fort Benning. She owned and operated two theatres in Rome, Georgia. She joined the Friendship Baptist Church, where her brother was a Deacon and she died at age 54, on December 22, 1939. She is buried at the Portersdale Cemetery in Columbus

There are plenty of people who seem willing to call her the "Mother of 'Classic' Blues" as opposed, apparently to "country" and "city" blues. Out here among the neck-down listeners we just call her terrific. And this, or some other collection, is absolutely essential to any collection of American Basics—this is one of those on our shelves that we like a whole lot.

The songs:

(Recorded October, 1924. Howard Scott—cornet, [probably] Don

Redman—clarinet, Fletcher Henderson—piano, Charlie Dixon—banjo. Session in

New York City.)

1. Jealous Hearted Blues

(Recorded October, 1924. Louis

Armstrong—trumpet, Buster Bailey—clarinet, Kaiser Marshall—drums on "Countin'

the Blues, Fletcher Henderson—piano, Charlie Dixon—banjo. Session in New

York City.)

2. See See Rider Blues

3. Jelly Bean Blues

4. Countin' the Blues

(Recorded December, 1925. Joe

Smith—cornet, Charlie Green—trombone, Coleman Hawkins—bass saxophone,

Buster Bailey—clarinet, Fletcher Henderson—piano, Charlie Dixon—banjo.

Session in New York City.)

5. Slave to the Blues

6. Chain Gang Blues

7. Bessemer Bound Blues

8. Wringin' and Twistin' Blues

(Recorded March, 1926. Jimmy

Blythe—piano. Session in Chicago.)

9. Mountain Jack Blues

(Recorded August, 1926. Lil

Henderson—piano. Session in Chicago.)

10. Trust No Man

(Recorded February, 1927.

Jimmy Blythe—piano, Blind Blake—guitar, Jimmy Bertrand—xylophone. Session

in Chicago.)

11. Morning Hour Blues

(Recorded December, 1927.

[Possibly] Shirley Clay—cornet, [possibly] Ike Rodgers—trombone, other

musicians and male voice unknown to us. Session in Chicago.)

12. Ma Rainey's Black Bottom

13. New Boweavil Blues

(Recorded June, 1928. The Tub

Jug Washboard Band, including: "Georgia Tom" Dorsey—piano,

[probably] Tampa Red—kazoo, banjo, jug and [possible] second kazoo unknown to

us. Session in Chicago.)

14. Black Cat, Hoot Owl Blues

15. Hear Me Talking To You

16. Prove It On Me

17. Victim of the Blues

(Recorded September, 1928.

Thomas Dorsey—piano, Tampa Red—kazoo. Session in Chicago)

18. Sleep Talking Blues

19. Blame It On the Blues

20. Daddy, Goodbye Blues

21. Sweet Rough Man

22. Black Eye Blues

23. Leavin' This Morning

24. Runaway Blues

(The

image is from the insert to the CD)

(The

image is from the insert to the CD)

(The pianist in this version of Ma's stage band is Georgia Tom Dorsey)

We offer the 1992 Milestone Records issue of Ma Rainey for $18.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

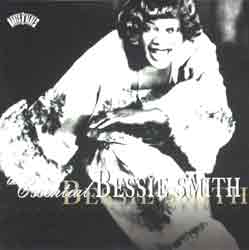

Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith

(We recommend:)

The Essential Bessie Smith

1997 Sony Music Entertainment release on CD

Roots and Blues Series Producer—Lawrence Cohn

(Cover image is from the CD)

By 1927 or 1928, "Ma" Rainey had purchased her

own bus to take her show on tours. Before she was done, Bessie Smith would have

her own railroad car.

Her date of birth, like so many things about her, is the subject of some controversy, but was likely to have been around 1894, in the Blue Goose Hollow section of Chattanooga, Tennessee. She and five siblings (some say more) were orphaned before she was 10, the family was reestablished in the Tannery Flats area by her sister Viola, and it is pretty well established that she was soon singing for change on the streets (and, quite possibly, in the bars) of the city while still a young girl.

Her brother Clarence had left town with a minstrel show in about 1904, and Bessie got her chance in 1912 when he returned to the area with the Moses Stokes troupe. He arranged an audition, she hired on as a dancer, and she lived in (and traveled out of) Atlanta until 1922. She became an Atlanta fixture at the 81 Theatre and traveled with tent shows and the black vaudeville circuit as far west as Oklahoma and as far north as New Jersey. By the time she moved north to Philadelphia in 1922 or '23, she had left the chorus line far behind and had her own solo act. She was a widow. And she was a blues singer.

She was also, apparently, a six-foot-plus, 200-pound package of Hell on Wheels. The blues were not an affectation for her. She very obviously lived the life and it showed up in many of the songs she wrote and sang. She still preferred bootleg whiskey even after Prohibition was repealed, went through two husbands and and a lot of other people, was stabbed in Tennessee, bailed Ma Rainey out of jail in Chicago, and sang the living crap out of "T'Ain't Nobody's Bizness if I Do."

Which was not, according to the credits on this album, written by Clarence Williams, although he is reported to have had a somewhat different opinion. What he did do, on the other hand, was set up recording sessions for Bessie at Okeh and Columbia Records in New York in 1921, where she was rejected. And after Columbia had basically fired the whole division and brought in Frank Walker, Williams got Bessie back to New York and, on February 15, 1923, played piano for her on the Alberta Hunter/Lovie Austin song "Downhearted Blues" and his own "Gulf Coast Blues."

"Down Hearted Blues" sold more than three-quarters of a million copies in the next six months and two million in a year. She got $125. But she cleaned up at the box office. By 1924, Bessie Smith was the most highly-paid black entertainer in America. She toured the East and South with her own show (and railroad car) and yes, she also toured the Midwest. She made more than 150 recordings.

And if she ever backed down to anybody, about anything, it has escaped the attention of her biographers.

The onslaught of the Depression after the Stock Market Crash of 1929 was not kind to blues singers or anybody else. Talking movies didn't help any. Musical tastes changed. By the time Prohibition ended in 1933, Bessie Smith had been with a bootlegger named Richard Morgan for three years and some called it love. In that same year, she had her last recording session. By 1937 she was a client of John Hammond and getting ready for a re-emergence, singing swing with Benny Goodman and others. Hammond scheduled a recording session and was scheduled to leave for Mississippi to bring her back to New York.

In the early morning of September 26,

1937, Bessie and Richard Morgan were driving near Clarksdale, Mississippi after

a show and rear-ended a truck parked on the side of Highway 61. The crash nearly severed Smith’s right arm. She was taken to G.T. Thomas Hospital (now the Riverside Hotel) in Clarksdale.

John Hammond claimed in writing that she had been turned away from a white

hospital because of her race. He later retracted the claim.

Bessie Smith was (probably) 43 years old. She is buried in Mount Lawn Cemetery in Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania.

Choice of this collection was a little difficult. Columbia chose not to include "Downhearted Blues" or "Empty Bed Blues" for some reason, but, on balance, this is the one recommended.

The songs:

Disk One

(Recorded April 11, 1923. Ernest Elliot—clarinet, [probably],

Clarence Williams—piano, Buddy Christian—banjo. Session in

New York City.)

1. Aggravatin' Papa

(Also recorded April 11, 1923. Clarence Williams—piano. Session in

New York City.)

2. Baby Won't You Please Come Home

(Recorded April 26, 1923. Clarence Williams—piano. Session in

New York City.)

3. 'Taint Nobody's Bizness If I Do

(Recorded September 21, 1923. Irving Johns—piano. Session in

New York City.)

4. Jail House Blues

(Recorded September 26, 1923. Jimmy Jones—piano. Session in

New York City.)

5. Graveyard Dream Blues

(Recorded April 5, 1924. Robert Robbins—Violin, Irving

Johns—piano. Session in

New York City.)

6. Ticket Agent, Ease Your Window Down

(Recorded April 7, 1924. Robert Robbins—Violin, Irving

Johns—piano. Session in

New York City.)

7. Boweavil Blues

(Recorded September 26, 1924. Joe Smith—Cornet, Charlie

Green—Trombone, Fletcher Henderson—piano. Session in

New York City.)

8. Weeping Willow Blues

(Recorded December 13, 1924. Charlie Green—Trombone, Fred

Longshaw—piano. Session in

New York City.)

9. Dying Gambler's Blues

(Recorded September 26, 1924. Louis Armstrong—Cornet,

Fred Longshaw—Reed Organ. Session in

New York City.)

10. St. Louis Blues

(Recorded January 14, 1925. Louis Armstrong—Cornet, Fred

Longshaw—Piano. Session in

New York City.)

11. You've Been a Good Old Wagon

(Recorded May 5, 1925 with Fletcher Henderson's Hot Six.

Joe Smith—Cornet, Charlie Green—Trombone, Buster Bailey—Clarinet, Coleman

Hawkins—Tenor Saxophone, Fletcher Henderson—Piano, Charlie Dixon—Banjo,

Bob Escudero—Tuba. Session in

New York City.)

12. Cake Walkin' Babies From Home

(Recorded May 26 and 27, 1925. Louis Armstrong—Cornet,

Charlie Green—Trombone, Fred Longshaw—Piano. Session in

New York City.)

13. Careless Love Blues

14. I Ain't Goin' to Play Second Fiddle

(Recorded November 18, 1925. Joe Smith—Cornet, Charlie

Green—Trombone, Fletcher Henderson—Piano. Session in

New York City.)

15. At the Christmas Ball

(Recorded March 18, 1926. Buster Bailey—Clarinet, Fletcher

Henderson—piano. Session in

New York City.)

16. Jazzbo Brown from Memphis Town

(Recorded February 17, 1926. James P. Johnson—piano. Session in

New York City.)

17. Backwater Blues

(Recorded March 2, 1927 with her band. Joe Smith—Cornet,

Jimmy Harrison—Trombone, Buster Bailey—Clarinet, Fletcher Henderson—piano. Session in

New York City.)

18. After You've Gone

Disk Two

(Recorded March 2, 1927 with her band. Joe Smith—Cornet,

Jimmy Harrison—Trombone, Coleman Hawkins—Clarinet, Fletcher Henderson—piano,

Charlie Dixon—Banjo. Session in

New York City.)

1. Alexander's Ragtime Band

(Recorded March 2, 1927 with her band. Joe Smith—Cornet,

Jimmy Harrison—Trombone, Buster Bailey—Clarinet, Fletcher Henderson—piano,

Charlie Dixon—Banjo. Session in

New York City.)

2. There'll Be a Hot Time In the Old Town Tonight

(Recorded March 3, 1927 with her Blues

Boys. Joe Smith—Cornet, Charlie Green—Trombone, Fletcher Henderson—piano. Session in

New York City.)

3. Trombone Cholly

(Recorded March 3, 1927 with her Blues

Boys. Joe Smith—Cornet, Charlie Green—Trombone, Fletcher Henderson—piano. Session in

New York City.)

4. Send Me to the 'Lectric Chair

(Recorded September 27, 1927. Porter

Grainger—piano, Lincoln M. Conaway—Guitar. Session in

New York City.)

5. A Good Man Is Hard To Find

(Recorded October 27, 1927. Tommy Ladnier—Cornet,

Fletcher Henderson—piano, June Cole—Tuba. Session in

New York City.)

6. Dyin' By the Hour

(Recorded August 25, 1928. Porter Grainger—piano,

Joe Williams—Trombone. Session in

New York City.)

7. Me and My Gin

(Recorded May 8, 1929. Clarence Williams—piano,

Eddie Lang—Guitar. Session in

New York City.)

8. Kitchen Man

(Recorded May 15, 1929. Ed Allen—Cornet,

Garvin Bushell—Alto Saxophone, Greely Walton—Tenor Saxophone, Clarence

Williams—piano, Cyrus St. Clair—Tuba. Session in

New York City.)

9. Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out

(Recorded June 9, 1930. James P. Johnson—piano,

The Bessemer Singers. Session in

New York City.)

10. On Revival Day (A Rhythmic Spiritual)

11. Moan, You Moaners

(Recorded July 22, 1930. Ed Allen—Cornet,

Steve Stevens—piano. Session in

New York City.)

12. Black Mountain Blues

(Recorded June 11, 1931. Louis

Metcalfe—Cornet, Charlie Green—Trombone, Clarence Williams—piano, Floyd

Casey—Drums. Session in

New York City.)

13. Shipwreck Blues

(Recorded November 20, 1931. Clarence

Williams—piano. Session in

New York City.)

14. Need a Little Sugar In My Bowl

(Recorded November 24, 1933 with Buck and

His Band. Frank Newton—Trumpet, Jack Teagarden—Trombone, Chu Berry—Tenor

Saxophone, Buck Washington—piano, Bobby Johnson—Guitar, Billy

Taylor—String Bass. Session in

New York City.)

15. Do Your Duty

16. Gimme a Pigfoot and a Bottle of Beer (Same

group, plus Benny Goodman on Clarinet)

17. Take Me for a Buggy Ride (Same

group, without Benny Goodman)

18. Down in the Dumps (Same group)

(The

image is from the back cover of the double CD issue)

(The

image is from the back cover of the double CD issue)

We offer the 1997 2-CD Columbia Legacy issue of The Essential Bessie Smith for $25.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

Dave

Macon

Dave

Macon

(We recommend:)

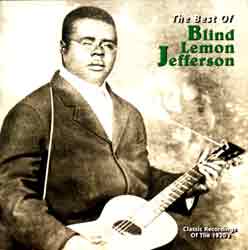

Lemon Jefferson

Lemon Jefferson

(We recommend:)

The Best of Blind Lemon Jefferson

2000 CD issue from

Yazoo

Produced by Richard Nevins

(Cover image is from the CD issue)

And all the time "the blues" were evolving

as a form that would sell millions of records and be offered from stages, they

were also being crafted on porches and streets and in bars and brothels and

passed from hand to hand. If you look at the musicians on those sessions with Ma

and Bessie, you'll find a history of early jazz as well, but under it all were

still the bluesmen and blueswomen with a guitar or a banjo or a jug or a diddley-bow...and those notes and words and feelings fed back into what was

happening on stages and in studios and, in a little while, in long desperate lines.

Which raises the question, "OK, which is the real blues?" ...And the answer we gave our kids, "I don't know...does it really matter?"

It sometimes seems like we're living our lives as if we're cramming for finals...as if information has to be squeezed into categories and lists that can be acronymically remembered, so it can be blurted into a blue book. Well, life's not like that. If we climb down out of our mental belfry and look around, we'll find that we live in a world of miracles and Mandelbrottian patterns, where everything relates to everything and that famous butterfly is king. And American music may be the very best example. A lyric line, a musical pattern, a catchy phrase...if a lone picker on a porch in Arkansas adds a new line to an AAB verse, can it change an election 50 or a hundred years later? If two stevedores on a river use chanted song and a bent-knee walk to pick up and carry something that weighs way more then they do, does a kid in Fargo or Hibbing pick up a Telecaster? How did a white harp and guitar player from the coal mining counties of West Virginia and a blind black street singer from Atlanta both come to use the same odd lyric when neither one of them probably had a phone and the Red and Blue Networks wouldn't play those songs?

But that's pretty heady stuff for someone who is still tuning the mental radio that seems to turn on at about age 10 to 13. So we like to build a fire and play them some songs by two blind men, both born around 1897 in a small area of Texas. The metaphor often used is that of American Basic music as a tightly braided rope, and the questions posed are "how far does that American musical rope reach?" and "how strong can it be if you leave out some of the big strands?" "Lemon" Jefferson is one of those two men. The other is "Willie" Johnson. And the answers are pretty amazing.

At the turn of the Twenty-First Century, the Interstates run out of Dallas, Texas like the legs of a striding man, forming two sides of a huge triangle. I35 runs southwest to Austin and San Antonio and the border, I45 runs southeast to Houston, Galveston and the gulf coast, and I10 runs out of Louisiana to link Houston to San Antonio and form the triangle's base. Freestone County lies near the top of that triangle, about 60 miles south of Dallas and northeast of Waco. Back at the turn of the Twentieth, it would have been described as being in the area between the Brazos and Trinity Rivers, 16 train stations south of Dallas on the Southern Pacific Line.

"Blind Lemon" Jefferson's proper name is lost in a Texas time without birth records. He was born to Alec and Cassie Jefferson near Wortham in Freestone County, in about 1897. He was blind (or barely sighted), probably from an early age (although he was fiercely independent and often made his own way in his travels) and had no formal education. He "took up" guitar and played the streets of Groesbeck, Buffalo and Marlin in the early 'teens. (We'll be coming back to the streets of Marlin when we get to "Blind Willie" Johnson in a bit.) Memphis had Beale Street. Dallas had "Deep Ellum," and sometime before he was 20, Jefferson moved to Dallas and played in the Deep Ellum District.

There is some dispute over whether Huddie Ledbetter and T-Bone Walker were really Jefferson's "guides" in those days. "Leadbelly" would have been about 10 years older, and they had different styles. What is known is that Ledbetter traveled widely from his birthplace in Louisiana and was also in Deep Ellum for a time before he pulled a prison term for murder between 1918 and 1924 in Texas, and that he recorded "Blind Lemon's Blues" in July, 1934 while at Angola Prison, back in Louisiana. If they didn't play the brothels of Texas together, Jefferson certainly knew where they were, and proved it in "Booger Rooger." Most seem to agree that Walker has the better claim to the "guide" distinction.

By 1925 he had been "discovered" by a Dallas retailer and talent scout named Sammy Price, and carried north to a Paramount Records (here we go again) studio in Chicago. In December of 1925 and January of 1926 he recorded two religious numbers as Deacon L. J. Bates. In March of 1926 he recorded four blues sides, and the sales of "Booster Blues/Dry Southern Blues" were good enough that Paramount released the other two. One was "Got the Blues." The other was "Long Lonesome Blues" and Jefferson was no longer a Texas street singer. The song tore open the envelope of "race" and blues records, and added the "itinerant, down-home" bluesman to the lexicon of successful styles. Between 1926 and 1928, Blind Lemon Jefferson was one of the most famous names in the field, with nearly 80 sides for Paramount reportedly selling over 100,000 copies each, and two sides for Okeh.

"Rabbit Foot Blues," "Prison Cell Blues," and "See That My Grave is Kept Clean" were all included on Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music, and Harry certainly had his reasons. Around here, we like "Hot Dogs" and a whole bunch of others equally well. It bears pointing out that about half of Jefferson's recordings were made without microphones or electrical amplification. And it might as well be mentioned that this ain't dance music...this is a singer/songwriter kicking down doors and limits and customs, cracking the one-song, one-octave barrier, and having a terrific time playing what he heard inside. But if you can't stand the sound of a fat needle on shellac spinning at 78 RPM, you're never going to get into this.

That would be a shame. For example, a lot of people have heard the digitally cleaned-up and remastered 1928 version of "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean" that was on Harry Smith's Anthology (and covered on Dylan's first album and a lot of others). But there aren't a lot of folks who have dug a little deeper through the crackles and hiss to the 1927 version recorded—like his first two sides—as Deacon Bates. And if you believe that all the strands making up that thick braid of American music need to be experienced...blues and jazz and spiritual and secular and all...you are going to find it a very interesting listen.

He is reported to have said (to Tom Shaw), "Get the sound in your head first, so that sound'll stay with you day and night. Then you learn to do somethin'. Until you get that sound in your head, shit, you ain't gonna do nothin'." A whole lot of people have had it between their ears, and some of them have sold a ton of records. Listen to Jefferson's "Match Box Blues." Then listen to Carl Perkins 1955 version or the Beatles track from September of 1964. (And then look closely at the writing credits on either of them.) And just for fun, track down Jefferson's 1929 versions of "Teddy Bear Blues" and then play Elvis Presley's "Let Me Be Your Teddy Bear."

After the Paramount sides started to sell, "Blind Lemon" Jefferson commuted between Dallas and Chicago, where he lived in a small apartment at 37th and Rhodes, and later at 45th and State. He died, probably of a heart attack, and possibly on the street, during a Chicago blizzard at the end of December, 1929. He was carried back to Texas and buried in Wortham on New Year's Day, 1930.

He rests in the Wortham Cemetery. His grave is a Texas state monument. It is kept very clean.

The songs:

(Recording dates are our best reconstruction...don't use 'em to settle any bets,

ok?)

1. Match Box Blues

(April, 1927 Chicago)

2. That Crawlin' Baby Blues

(September, 1929 Richmond, Indiana)

3. Hot Dogs

(June, 1927 Chicago)

4. Corinna Blues

(May, 1926 Chicago)

5. Rambler Blues

(September, 1927 Chicago)

6. Rabbit Foot Blues

(December, 1926 Chicago)

7. Dry Southern Blues

(March, 1926 Chicago)

8. 'Lectric Chair Blues

(February, 1928 Chicago)

9. One Dime Blues

(October, 1927 Chicago)

10. Got the Blues

(May, 1926 Chicago)

11. See That My Grave Is Kept Clean

(October, 1927 Chicago)

12. He Arose From the Dead

(June, 1927)

13. Black Horse Blues

(April, 1926 Chicago)

14. Prison Cell Blues

(February, 1928 Chicago)

15. Booster Blues

(March, 1926 Chicago)

16. Bed Spring Blues

(September, 1929 Richmond, Indiana)

17. Jack O' Diamond Blues

(May, 1926 Chicago)

18. Beggin Back

(August, 1926 Chicago)

19. Wartime Blues

(November, 1926 Chicago)

20. Easy Rider Blues

(April, 1927 Chicago)

21. How Long How Long

(July, 1928 Chicago)

22. Long Lonesome Blues

(March, 1926 Chicago)

23. I Want to be Like Jesus In My Heart

(December, 1925 Chicago)

(The

image is from the back cover of the CD)

(The

image is from the back cover of the CD)

We offer the 2000 Yazoo Records CD issue of The Best of Blind Lemon Jefferson for $18.00 US plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

Frank

Hutchison

Frank

Hutchison

(We recommend:)

Complete Recorded Works

Volume 1—1926-1929

1997 Document Records release on CD

Produced by Johnny Parth

(Image is from the CD insert cover)

From the Saint Louis Globe Democrat

(Probably December 29, 1895)

"William Lyons, 25, a levee hand, was shot in the abdomen yesterday evening at 10 o'clock in the saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan Streets, by Lee Sheldon, a carriage driver. Lyons and Sheldon were friends and were talking together. Both parties, it seems, had been drinking and were feeling in exuberant spirits. The discussion drifted to politics, and an argument was started, the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon's hat from his head. The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon withdrew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen. When his victim fell to the floor Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away. He was subsequently arrested and locked up at the Chestnut Street Station. Lyons was taken to the Dispensary, where his wounds were pronounced serious. Lee Sheldon is also known as 'Stag' Lee."

Billy Lyons died, and, two trials later, Stag Lee Sheldon was sent to prison. He died sometime between 1910 and 1920.

If you grew up in America in the 1940s and '50s there were a sheaf of unwritten rules. Only the rare adult would tell you what any of them were. You had to figure them out for yourself based on what you saw and heard, and pieces picked up from the universal children's conspiracy. They didn't make sense, on the face of things, but they were real. Out in buffalo grass country, for instance, you didn't touch a man's hat without his permission... And a hat was a hat, but a Stetson was a hat.

So just how big IS that blasted butterfly?? Anyway? And how deep do the musical currents run? We later heard that Wild Bill Hickok once shot a man for touching his hat, but that was well before Stag Lee Sheldon shot his way into myth and the river of songs. We don't know how much of that one's true, either. But you start to wonder. Where does this stuff come from and where does it go?

A lot of us grew up on legends—Pecos Bill, Paul Bunyon and Johnny Inkslinger, Casey Jones, John Henry, Johnny Appleseed... Stag Lee and Barnacle Bill and Old John and Po' Shine and Old Riley took a while to get to us but when they did, they fit right in... And everybody knew about the Hatfields and the McCoys, but nobody would say much about the Gray Goose Roadhouse in the middle of the prairie right near the exact center of the continent, a little bit north of Pierre...

Frank Hutchison was born March 20th, 1897 in Raleigh County, West Virginia, (not too far from the Blue Goose) a little over a year after Billy Lyon died in Missouri. He started playing harmonica at the age of eight and became a coal miner—hardly unusual in that part of the state. The story goes that he learned blues music when he was growing up by watching a disabled black man named Bill Hunt. Another black musician, named Henry Vaughn, was probably also an early influence. By the mid-19-teens he was augmenting his income by playing music, which was at least marginally safer than being in or around the mines near Matewan, Mingo County, Logan County and Blair Mountain. He played slide guitar with the instrument held in his lap and a knife on the neck, harmonica with a neck rig, and sang both songs he knew and songs he wrote. He played "mountain" music and ballads with others and blues by himself in small towns and mining camps along the West Virginia-Kentucky border.

Some say he was the first white bluesman to make records—32 sides for Okeh between 1926 and 1929. He's the first one we know of around here. But if you think that's all there is to the story, then you quit reading quite a while ago.

At the end of September, 1926, he sat down in a non-electric studio and recorded two of the songs he learned from Bill Hunt—"Worried Blues" and "Train That Carried the Girl From Town." The slide work has been described by people a whole lot smarter than us as "devastating" [Tony Russell's liner notes, 1997] and it's too darn bad the session wasn't miked. Four months later, on January 28, 1927, he cut nine more sides. They included both an instrumental and vocal version of "Stackalee," some very serious picking and harmonica work on three other instrumentals, and a vocal that would turn into "(I'm Goin' Back to) 'Alabam" in the hands of Lloyd "Cowboy" Copas and Pat Boone in 1960. Pat Boone!?! (...uh huh...)

Twenty-three months later, on December 28, 1928, Mississippi John Hurt sat down in another Okeh studio, in the middle of another New York City winter, and recorded "Stack O' Lee." Play them back-to-back sometime. And think about that "Stetson hat" the two of them mention...

But in the meantime, Frank Hutchison had gone into a studio in Saint Louis (yep!), in April of 1927 and cut four sides, this time electrically. The first one was "Worried Blues." And, if Greil Marcus is to be believed, the culture shifted down at the other end of the century. One of these days we have to put Invisible Republic up, over on the bookshelves.

In the fall of 1929, he made his last recordings and never returned to the studio after the Depression. Some say he played on steamboats for a while. He and his wife moved to Chesapeake, Ohio and then back to run a store in the town of Lake in Logan County, about 10 miles or so from Dog Patch and eight from Logan, until the store burned down. He died on November 9, 1945 in Columbus, Ohio.

In 1952, Harry Smith put Hutchison's vocal version of "Stackalee" on Volume 1 of the Anthology of American Folk Music and there's a whole lot more to that story as well. That's all better done in person though, along with a heck of a tale about what Lloyd Price was up to from 1952 to '56 while some of us were sitting close to a coal-oil-burning stove in a one-room school somewhere out on the buffalo grass...

If you're of a mind to, sit down by a stove some winter night when it's blacker outside than a coal miner's nosehairs and colder than a witch's brass monkey, and put this thing on. Turn it way up, tip back, close your eyes and try to set your watch back 75 years. Then listen to "Logan County Blues" and "The West Virginia Rag" and "Worried Blues" and "Stackalee" and anything else you want to punch in there. Close your session with "Hutchison's Rag." Tip one to the miner if you wish, and realize that you just shared part of an experience with Leo Kottke and Spider John Koerner and Doc Watson and Cowboy Copas and a whole lot of other pickers and players and hard listeners. Including Bob Dylan, of course...

And that ain't bad company, folks.

The songs:

(Recorded September 28, 1926. Session in

New York City.)

1. Worried Blues (80143)

2. Train That Carried the Girl From Town (80144)

(Recorded January 28, 1927. Session in

New York City.)

3. Stackalee (30350)

4. The Wild Horse

5. Long Way to Tipperary

6. The West Virginia Rag

7. C&O Excursion

8. Coney Isle

9. Old Rachel

10. Lightning Express

11. Stackalee (80359)

(Recorded April 28 and 29, 1927. Sessions in

Saint Louis, MO.)

12. Logan County Blues

13. Worried Blues (80782)

14. The Train That Carried the Girl From Town (80783)

15. The Last Scene of the Titanic

16. All Night Long

(Recorded September 10, 1928. Sherman

Lawson—Fiddle. Session in

New York City.)

17. Alabama Girl, Ain't You Comin' Out Tonite

18. Hell Bound Train

19. Wild Hogs in the Red Brush

(Recorded September 11, 1928. Session in

New York City.)

20. The Burglar Man

21. Back in My Home Town

22. The Miner's Blues

23. Hutchison's Rag

(Recorded July 9, 1929. Session in

New York City.)

24. The Boston Burglar

(The

image is from the Library of Congress)

(The

image is from the Library of Congress)

(Coal mine in Logan County, West Virginia)

We (will) offer the 1997 Document Records issue of Frank Hutchison, Complete Recorded Works—Volume 1 (1926-1929) for $30.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

[This title is out of publication, and we've been forced to take it down for a little while. We're assured by Document that it is not out of print. They just don't have any right now. We're keeping a waiting list.]

Will

Shade and the Memphis Jug Band

Will

Shade and the Memphis Jug Band

(We recommend:)

The Best of the Memphis Jug Band

2001 Yazoo Records release on CD

(Cover image is from the CD)

The trail of the kazoo...

The music knows.

It knows what's going on and what happened. It knows our truths and our secrets, our solitary whispers and hollers, our glories, our lies and our shame and our pride. It knows what we deserve, and it knows what we need. And sometimes it knows what's coming before we do...

Don't try to tell us that the music reflects the times. It isn't just a mirror...it's a player. It's our collective voice. It's stuff we can't speak out loud. It's stuff we haven't consciously realized yet but we already know. If there really is an American people—and there is—then the music may just be the voice of the difference between the whole and parts. It speaks, it comforts, it teaches, and it allows us to all wake one morning as a people better than the night before.

And the music never forgets.

Harry Smith said, "I'd been reading Plato's Republic. He's jabbering on about music, how you have to be careful about changing the music because it might upset or destroy..." Don McLean said the music could die and we spent the winter of 1971-72 trying to figure his lyrics out. For two months in the summer of 1966, Sue Christie said "I Love Onions," on every radio button in your car, and none of us could figure out why that kazoo was so darn infectious. Anyway...

New Orleans had Storyville. Dallas had Deep Ellum. Memphis had Beale Street. But somewhere between the back porches in the country and the "hot" districts in the cities, there was another tradition...the open, public gathering place. Music comes to gathers...always has...and sometimes it will be denser in one place for a time.

The mountain men and trappers came to rendevous...and it wasn't just about furs and whiskey. The northern tribes had gathers in the spring and fall with their own rules and songs. New Orleans had Congo Square in the 1800s. And Church's Park (now W. C. Handy Park), not too far from Pee Wee's, was where the music came in Memphis, at least until the Depression let the air out of Beale Street for a while after 1930.

Will Shade was born in Memphis in 1898 and learned to play guitar from Tee Wee Blackman.

The story goes that up on the Ohio, above the joining with the Mississippi at Cairo, a whole series of things had coalesced in Louisville around the time of Will's birth, and something called the "jug" band had become a tradition, playing at black and white gatherings, including the Kentucky Derby. The roots of the Memphis jug bands have also been traced to an 1898 encounter between B. D. Tite and a musician called "Black Daddy" (both from that city) with a jug blower in Virginia. Other sources mention jug bands in Mississippi as early as 1901. Some say that the Sara Martin Jug Band was the first such to record, in 1923 or '24, and she was, indeed, from Louisville originally. Some say the first jug band from Louisville to be recorded was (appropriately) the Louisville Jug Band (aka the Dixieland Jug Blowers, led by Earl McDonald and violinist Clifford Hayes)— on Black Swan Records in 1926 in Chicago.

There are a lot of stories. Few of them agree.

Meanwhile, back in Memphis, Will Shade had been raised by his grandmother, Annie Brimmer. He had picked up a nickname—"Son" Brimmer—which was also a play on words for a type of hat and would work its way into his music. He had played the streets of Memphis with Furry Lewis in the late 'teens. Shade was playing in medicine and minstrel shows by the 1920s and also started playing the streets in the mid-'20s with "Lionhouse," who played an empty whiskey bottle. They did well enough in tips that Shade got Lionhouse a gallon jug and formed a band. It's not documented, but you know where he went...Church's Park. What is known is that Shade tailored the personnel makeup for dates and recording sessions, and a lot of musicians played with the group between its first recordings in February, 1927 and the last in 1934. He played guitar, harmonica and bullfiddle (tub bass) and was the constant member of the band's orbiting makeup. Others included Will Weldon on guitar, Vol Stevens on vocals and stringed instruments, Tee Wee Blackman, fiddle players like Charlie Pierce and Will Batts, and jug players and kazoo players like Ben Ramey, Charlie Polk, Ham Lewis and Jab Jones, the pianist. Charlie Burse joined the group in 1928, and was a constant member from that time on, playing guitar and mandolin.

Shade also included a number of vocalists from the Memphis area, including Hattie Hart, Charlie Nickerson and Memphis Minnie.

As the Depression and the number of crackdowns on the Beale Street fast life both grew, times also grew hard for musicians in Memphis. The Memphis Jug Band moved in the direction of hokum and up-tempo songs like "Insane Crazy Blues" and the incredible "Memphis Shakedown" in their final, 1934 recordings.

This collection includes songs from The Memphis Jug Band recorded between 1927 and 1934, although it does not include the very first recording, "Sun [Son] Brimmer's Blues." It includes a 1930 recording with Memphis Minnie singing and playing guitar on "Meningitis Blues."

Will "Son Brimmer" Shade died in Memphis on September 18, 1966. Around here we really, really hope he got some chuckles from the kazoo-driven sound that saturated the airwaves in the months before his death. He is buried in the Shelby County Cemetery. Charlie Burse passed the previous year on December 20th, and is buried in the Rose Hill Cemetery.

Jug band music is the emotional penicillin of the huge span of "American Basic" music covered by a wide number of imposed "categories" that includes blues. Jug bands can be compared to the chorus in Greek drama, to some pretty good effect. Elsewhere in these pages there have been words about the teachings that come up from the ancient truths of the land about the need to balance everything. The old ways would hold that if you want some part of your home-made music to be profound, you're also going to have some that's a little goofy. Around here, we're not sure that there isn't about as much history and profundity in this stuff as in anything else.

A lot of people like Lucinda Williams and Jerry Garcia have apparently agreed with us. The Dead did at least three of the songs that originated with Will Shade and the Memphis Jug Band. Harry Smith put "K. C. Moan," "Bob Lee Junior Blues" and "Memphis Shakedown" on the Anthology of American Folk Music.

And you have to wonder what people who don't own one, single album of jug band music do on those periodic mornings that come to everybody...when you can't stay in bed and you can't face the day...

This stuff (or Cannon's Jug Stompers....or both) isn't just American basic. It's darn-well American essential.

The songs:

1. Tired of You Driving Me

(1929)

2. A Black woman is Like a Black Snake

(1928)

3. Aunt Caroline Dyer Blues

(1930)

4. Popa's Got Your Water On

(1930)

5. On the Road Again (1928)

6. K.C. Moan (1929)

7. Cocaine Habit Blues (1930)

8. Coal Oil Blues (1928)

9. You May Leave, But This Will Bring You Back

(1930)

10. Memphis Yo Yo Blues (1929)

11. Memphis Shakedown (1934)

12. She Stays Out All Night Long (1928)

13. Meningitis Blues (1930)

14. Stealin' Stealin' (1928)

15. He's In the Jailhouse Now (1930)

16. Taking Your Place (1929)

17. Ambulance Man (1930)

18. Beale Street Mess Around (1927)

19. Going Back to Memphis (1930)

20. State of Tennessee Blues (1927)

21. Insane Crazy Blues (1934)

22. Memphis Jug (1927)

23. Got a Letter From My Darlin' (1930)

(The

image is from the back cover of the CD)

(The

image is from the back cover of the CD)

(Peewee's Place in Memphis)

We offer the 2001 Yazoo Records issue of The Best of the Memphis Jug Band for $18.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

W.

J. Johnson

W.

J. Johnson

(We recommend:)

The Complete Blind Willie Johnson

1927-1930

1993 Columbia/Legacy Records release on CD

Roots N' Blues Series Producer Lawrence Cohn

(Cover image is from the CD)

...Old roads of broken macadam, gravel and iron remember, too...

Things take on a life of their own, sometimes. This is a good place to make a small confession. When this whole enterprise was first being considered, a huge pile of old vinyl was pulled out and played and puzzled over. We looked at artists who could be considered jazz, folk, country, bluegrass, pop, blues... collections...you name it. There was going to be a Blues Collection, a Jazz Collection—you get the idea. But the singers of the spirit never came off those (real) shelves upstairs. No Bessie Griffin in the pile. Nothing from Sister Tharpe. And Willie Johnson stayed up there with the others, too.

Some of us remember baking-hot trips across the plains in family cars with running boards and a canvas water bag hanging off a hood latch. A few of those remembered journeys even had music—from radios with an antenna aiming knob above the windshield center—eclectic offerings in the gradually fading signals of small AM stations. And there was something persistent about those memories of the smell of metal dashboards and dusty cloth seats on 110-degree days on the prairie. They wouldn't let themselves be set aside, and kept popping to mind like a kitten tugging at a cuff. So we laid out a trip across a dry July in Southern Minnesota and South Dakota with some of the reissue CDs chosen, in a 30-year old Lincoln Mark IV with a rebuilt V-8 and a new sound system. The windows were down. The air conditioning was left off. The radio was banned for the duration. The roads were two-lanes with state and federal numbers from the twenties and thirties. It was unclear what we were looking for, but it felt right.

The first music loaded up, when the sprawl was well behind, was Harry Smith's Anthology...all six disks...in order. Yep, 70-year-old music, from a 50-year-old compilation, in a 30-year-old Lincoln—rumbling past abandoned farmhouses and ancient hand-laid railbeds—on rural roads through hills older than history. And when Clarence Ashley and Uncle Eck and Furry Lewis and Charlie Patton and the others came out of the speakers, you could smell the old stories the hot winds were carrying in through the windows.

Exactly half-way through, came a thundering reminder that if you're serious about that densely-braided metaphorical rope we've been calling the American soundtrack, you cannot just leave out a huge sheaf of strands.

When Harry put together the Anthology in 1952, he divided it into three volumes of two LPs each. The second volume was Social Music. The first record in that volume was frolics and reels and stomps and it ended with "Newport Blues" by the Cincinnati Jug Band and "Moonshiner's Dance" by Frank Cloutier. That's pretty "social." But when the second record of the second volume dropped down off the spindle, Harry took you to church ... with Rev. J. M. Gates and the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers and the Carter Family among a lot of other "large" groups. And that's social, too.

And down near the end of the second side of that second record, Smith dropped in one song by one predominant voice in a duet with guitar accompaniment, together with a mystery stated in a contradiction. "No information is available on Willie Johnson, one of the most influential of all religious singers." The song was "John the Revelator."

In that old Lincoln, it was like getting hit between the eyes. Somehow or other, the shelf selections had gotten secularized. The best story in the music, the answer to the question "How far can the music of the American folk reach," had been left upstairs on the shelves. It was a bit like being transported back to the streets of Marlin, Texas in the nineteen-teens and choosing to only face one way...

It's 135 miles from Wortham south to Brenham. In the middle, down there between the Brazos and the Trinity Rivers south of Dallas, is Marlin. "Blind Lemon" Jefferson had been born in Wortham in (probably) 1897. "Blind Willie" Johnson was born in Brenham in the same year. By the time they were in their teenage years they were singing on opposite street corners on the dusty, cotton-country streets of Marlin. One sang blues. The other didn't.

Eighty years later, something tugged at our attention and we parked on the crumbling macadam in Vivian, South Dakota at the intersection where the old railroad tracks cross main street. Looking off to the west from the abandoned way station, you can see the railbed gradually fade beneath the prairie and disappear, like a river sinking underground.

Blind Lemon Jefferson's first two recorded songs in 1925 and 26 were religious, under the name Deacon L. J. Bates. And "See That My Grave is Kept Clean" was first recorded as Deacon Bates in 1927, a year before the version everyone knows. But it was the fast-life blues songs that brought him fame and laid down the template for the solo blues man. "Long Lincoln Land" in "Booger Ooger Blues" was a red light district and "Black Snake Blues" isn't about a reptile.

On the other street corner, both the one in Marlin all those years ago, and in that westward-rolling Mark IV, was the other man and the music that was not about to be left out...

So W. J. Johnson is one of the reasons this collection is now called "American Basics." He wouldn't have wanted to be included on a "Blues" shelf. There's not a "secular" song in his recordings, and that's going to put a lot of people off, to their very great loss. Because Mr. Johnson's angels have guitar calluses and the songs they whispered to his mind aren't necessarily ethereal. But we dare you to really listen the second time around on these disks...to the sounds and the feeling and the technique and depth of his music and vocals...and then tell anybody that he doesn't belong right here...running a way-station on the roadbed of the nation's memory.

For a religious man, he has been the source of a lot of disputation as people tried to fill in the mystery raised by Harry Smith. When was he born, when did he die, where is he buried, who sang the duet on "Soul of a Man?" And on "John the Revelator?"

Recently discovered documents show he was born in 1897 near Brenham. His father, George Johnson, moved them to Marlin and, later, brought him to Hearne where George worked in the brickyards and Willie sang on the streets. And those were also the years when a Saturday afternoon in Marlin would find him singing on the same streets as Blind Lemon Jefferson. In about 1926 or 1927, he married Willie B. Harris, and it's her voice in the duets he recorded, except for the New Orleans session. It was discovered in 2002 that they had a daughter, when Sam Faye Johnson Kelly was found living quietly in Marlin. At some point in the early 1930s he began a relationship with and likely married Angeline Johnson, remaining with her until his death.

Blind Willie Johnson recorded 30 songs, in five sessions, between December 3, 1927 and April 20, 1930. A lot of serious players, like Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Duane Allman have spoken of their debt to him and you can hear his influence among his contemporaries from Robert Johnson to Son House and Muddy Waters. Our resident folk scholar, Thomas E. Barrett (Catfish-watcher extraordinaire), also points out that "If I Had My Way (I Would Tear This Building Down)" appeared on both Peter, Paul and Mary's first album and their live album (credit to Rev. Gary Davis), and that they included "Go To Me With That Land" with a slightly rearranged title on the 1965 album A Song Will Rise.

Oh...And how far can the music reach? Over eight and a half BILLION miles and counting, thanks to W. J. Johnson.

In 1977, America launched Voyager I on a mission to interstellar space...beyond the heliopause boundary where the sun's influence ends. On board is a record player and some recordings...rain, a heartbeat, Bach, Beethoven....and "Dark was the Night—Cold was the Ground" as played and sung by "Blind Willie" Johnson. When Ry Cooder, who's a pretty fair player himself, wrote the haunting soundtrack to the movie "Paris, Texas," he based the entire work on "Dark was the Night..." He described Johnson's song as "The most soulful, transcendent piece in all American music."

You can't paint the American dream with one brush or mix the songs we wake up with down to one track. And if you want to search out who we were—and are—you need to walk the hushed, three-in-the-morning borders along the roadbeds of our common heritage past Mr. Johnson's way-station. You can't take anything that isn't given while you're there. You need to be careful what you leave out when you're passing it on to your kids and friends. We almost forgot that.

In 1945, Willie and Angeline were living at 1440 Forest Street in Beaumont, Texas when their house burned. Angeline recalled many years later that, "...we didn't know many people, and so I just, you know, drug him back in there and we laid on them wet bed clothes with a lot of newspaper. It didn't bother me but it bothered him." Blind Willie Johnson died of pneumonia. His death certificate says that he is buried in the now-neglected Blanchette ("colored") Cemetery in Beaumont. There is no headstone. When the cemetery floods wooden coffins can sometimes be seen floating away on the water.

Somewhere about 300 hot miles into a thousand on those old roads far to the north of Beaumont, it became clear that a lot of things don't change much. The hills and the grass and the restlessly breathing winds of the plains have seen it all, and they are pretty much the same now as in the twenties and thirties. Willie Johnson knew back then how important some questions were. He laid them down for all of us, because they don't change, either. Like, "What is the soul of a man...."

And, "Are we alone?"

The songs:

Disk One

(Recorded December 3, 1927 in Dallas.)

1. I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole

2. Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed

3. It's Nobody's Fault But My Own

4. Mother's Children Have a Hard Time

5. Dark Was the Night—Cold Was the Ground

6. If I Had My Way I'd Tear the Building Down

(Recorded December 5, 1928 in Dallas.)

7. I'm Gonna Run to the City of Refuge

8. Jesus Is Coming Soon

9. Lord I Can't Just Keep From Crying

10. Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning

(Recorded December 10, 1929 in New

Orleans.)

11. Let Your Light Shine On Me

12. God Don't Never Change

13. Bye and Bye I'm Goin' to See the King

14. Sweeter As the Years Roll By

Disk Two

(Recorded December 11, 1929 in New

Orleans.)

1. You'll Need Somebody On Your Bond

2. When the War Was On

3. Praise God I'm Satisfied

4. Take Your Burden to the Lord And Leave It There

5. Take Your Stand

6. God Moves On the Water

(Recorded April 20, 1930 in Atlanta.)

7. Can't Nobody Hide From God

8. If It Had Not Been For Jesus

9. Go To Me With That Land

10. The Rain Don't Fall On Me

11. Trouble Will Soon Be Over

12. The Soul Of a Man

13. Everybody Ought To Treat a Stranger Right

14. Church, I'm Fully Saved To-Day

15. John the Revelator

16. You're Gonna Need Somebody On Your Bond

We offer the 1993 Columbia/Legacy issue of The Complete Blind Willie Johnson for $20.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

Son House

(We recommend:)

Furry Lewis

(We recommend:)

Moran Lee (Dock) Boggs

(We recommend:)

William

Broonzy

William

Broonzy

(We recommend:)

Big Bill Broonzy in Chronological Order

Volume 1 (1927-1932

1991 Document Records release on CD

Compiled and Produced by Johnny Parth

(Cover image is from the CD)

The songs:

(Recorded November, 1927. Paramount

session in Chicago)

1. House Rent Stomp

(Recorded February, 1928. Paramount session in

Chicago)

2. Big Bill Blues

(Recorded October, 1928. Paramount session in

Chicago)

3. Down in the Basement Blues

4. Starvation Blues

(Recorded April 9, 1930. Perfect Records

session in New York City)

5. I Can't Be Satisfied

6. Grandma's Farm

7. Skoodle Do Do

(Recorded April 11, 1930. Perfect Records

session in New York City)

8. Tadpole Blues

(Recorded May 2, 1930. Session in Richmond,

Indiana)

9. Skoodle Do Do

10. Saturday Night Rub

11. Pig Meat Strut

12. Papa's Gettin' Hot

(Recorded September 16, 1930. Session in

New York City)

13. Police Station Blues

14. They Can't Do That

(Recorded September 17, 1930. Session in

New York City)

15. State Street Woman

16. Meanest Kind of Blues

17. I Got the Blues For My Baby

(Recorded November 19, 1930. Session in

Richmond, Indiana)

18. The Banker's Blues

19. How You Wan't Done

(Recorded February 9, 1932. Session in

Richmond, Indiana)

20. Too Too Train Blues

21. Mistreatin' Mama

22. Big Bill Blues

23. Brown Skin Shuffle

24. Stove Pipe Stomp

25. Beedle Um Bum

26. Selling That Stuff

We offer the 1991 Document Records issue of Big Bill Broonzy in Chronological Order, Volume I (1927-1932) for $22.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

John Hurt

John Hurt

(We recommend:)

Mississippi John Hurt

Avalon Blues: The Complete 1928 Okeh Recordings

1996 Sony Music Entertainment release on CD

Roots and Blues Series Producer—Lawrence Cohn

(Cover image is from the CD)

It sometimes occurs to us that if the quantum

butterfly of American music has a face, it would look a lot like that of John

Smith Hurt.

In the days when you had to wind your watch, the best ones had jewels at the critical pivot points, because they wore so well. Same here.

In the 1920s, Hurt carried Scotch-Irish "hill music" sounds into the blues and in the 1960s his style fed back into the finger-picking styles of the folk and blues revivals.

Although Hurt was from Mississippi, and a contemporary of folks like Charlie Patton, his music was different.

The songs:

(Recorded February 14, 1928. Session in

Memphis, TN...although some say....)

1. Frankie

2. Nobody's Dirty Business

(Recorded December 21, 1928. Session in

New York City.)

3. Ain't No Tellin'

4. Louis Collins

5. Avalon Blues

6. Big Leg Blues

(Recorded December 28, 1928. Session in

New York City.)

7. Stack O' Lee

8. Candy Man Blues

9. Got the Blues (Can't Be Satisfied)

10. Blessed Be the Name

11. Praying on the Old Campground

12. Blue Harvest Blues

13. Spike Driver Blues

(The

image is from the CD insert)

(The

image is from the CD insert)

We offer the 1996 Columbia Legacy issue of Mississippi John Hurt, Avalon Blues: The Complete 1928 Okeh Recordings for $15.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]() (We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

(We

are currently refurbishing and expanding the record shelves and changing over to

a completely integrated payment system for our customers, but we will be happy

to honor orders received by e-mail during this interim. Click

button to send us your orders or comments.)

Thomas Dorsey

Thomas Dorsey

(We'll probably recommend:)

Georgia Tom Dorsey

1928-1932

Come On Mama Do That Dance

1992 Yazoo release on CD

(No named producer)

(Cover image is from the CD)

Sourcing on this one is a little problematic right now. We're making a final selection for the early recordings of Mr. Dorsey.

The songs:

Disk One

1. Mississippi Bottom Blues

Tom Dorsey

2. Jive Man Blues

Frankie Jaxon

3. How Can You Have the Blues?

Kansas City Kitty and Georgia Tom

4. But They Got It Fixed Right On

Tampa Red and Georgia Tom

5. Crow Jane Alley

Georgia Tom and Tampa Red

6. Gym's Too Much for Me

Kansas City Kitty and Georgia Tom

7. If I See My Saviour

Georgia Tom Dorsey

8. Rollin' Mill Stomp

Georgia Tom Dorsey

9. Some Cold Rainy Day

Bertha "Chippie" Hill

10. Come on Mama

Jane Lucas and Georgia Tom

11. Devilish Blues

Stovepipe Johnson

12. Second-Handed Woman Blues

Georgia Tom Dorsey

13. The Doctor's Blues

Kansas City Kitty and Georgia Tom

14. How About You?

Georgia Tom Dorsey

We plan to offer the 1992 Yazoo issue of Georgia Tom Dorsey: Come On Mama Do That Dance for $25.00 US, plus shipping and handling.

![]()

(Click button to add to your cart or wishlist. Not hot yet...we're working on it.)

Tampa

Red

Tampa

Red

(We'll probably recommend:)

1928-1942...It's Tight Like That

1994 Story of the Blues release on CD

Produced by Riki Parth

(Cover image is from the CD)

Sourcing on this one is a little problematic right now. We're making a final selection for the early recordings of Tampa Red.

The songs:

Disk One

1. (Honey) It's Tight Like That

2. Big Fat Mama

3. Juicy Lemon Blues

4. Uncle Bud

5. How Long, How Long Blues

6. It's Tight Like That

7. Kunjine Baby

8. Friendless Gal Blues

9. Death Cell Blues

10. Have You Ever Been Worried In Mind—Part 1